Child of the Century

by Barbara Brooks

Eleanor Dark is a writer whose work lies at some central point, some pivotal place in this century. Born in 1901, she lived through, and recorded in her novels, the major events of the first half of the twentieth century: two wars, the Great Depression of the 1930s, the Cold War and fear of a nuclear holocaust. She wrote about indigenous rights, environmental degradation, the changing situation of women, social justice. One of a generation of writers who had a dream of what this country and culture could be, she gives us a lens through which we can see not just the past but also the deep present. There are tracks we can follow, we can know how we came to be here now.

She published ten novels, in seven countries, as well as stories, poems, articles and essays; her work was recognised by literary awards while her novels, particularly The Timeless Land, had a wide readership. She was writing at the time when a publishing industry was developing in Australia; when local writers fought for recognition, and women writers, who almost dominated the scene in the 1930s, acknowledged in their letters to one another the silence and difficulty of parts of their lives, the struggles for justice as well as the achievements.

Eleanor & Eric Dark come to Varuna

The first house sits in the hollow of the heart, Dorothy Hewett wrote. The house that sat in the hollow of Eleanor Dark's heart was Varuna, where she lived for more than sixty years, and wrote most of her novels. In 1923, in the wake of the Great War, the "rosy, pleasure-mad" years before economic depression, Eleanor and Eric Dark came to Katoomba, in the Blue Mountains. Varuna then was a weatherboard cottage in 2 acres of wild garden surrounded by big pines.

Like other writers and artists before and after them, they moved from the city looking for space, peace, and cheaper living, in search of a place where they could make the kind of life they wanted. They were thoughtful, generous people, non-conformists; they led rather austere lives in a beautiful environment. Ideas were important to them: books, writing, social justice; and they admired people who put ideas into practice rather than following the crowd.

Eleanor was a striking looking woman with tremendous vitality, an expressive face and eyes, charming when she liked people and haughty when she didn't. She had an incisive intelligence as well as a strong belief in intuition. When they married, she told Eric she wanted an equal partnership, a child, and the freedom to write. Eric was 33 then, small, wiry, and energetic, a "red-headed bloke with eyebrows like steamshovels". Deeply affected by his war experiences, he was an idealist with a practical temperament, a doctor with a weakness for flash cars, and a skilled and daring climber. And he was in love with a woman he was confident would be a great writer.

Pixie O'Reilly & Eleanor Dark

Eleanor Dark was born Eleanor O'Reilly in Sydney in 1901. Her father was Dowell O'Reilly, poet, short story writer, and politician; he gave her the nickname "Pixie". Her mother was a shadowy figure, both physically and emotionally distressed by an unhappy marriage and lack of money, sick for several years before she died, in 1916, when Eleanor was only 13. Eleanor went to Redlands boarding school, then worked as a typist in an office. She married Eric Dark in 1922.

When they came to Katoomba, Eleanor had already started writing. She was publishing poems and stories in magazines, as P. O.'R. or Patricia O'Rane - she said she used a pseudonym to avoid being identified with her father. Payment for a poem for was about price of a bag of manure for the garden. She was already working on two novels; she published Slow Dawning in 1932. Eric had a son, John, from his first marriage to Kathleen Raymond, who died soon after her child was born; John came to live with them. Michael, their son, was born in 1929.

Never enough time to write

Between looking after the children, the house, and answering the doctor's phone, Eleanor said she could never find enough time at her desk. Throughout her life, she wrote about the struggle for uninterrupted time:

"I'm ploughing along with a new book, but often don't get to it for a week at a time, and find it hard to pick up the threads again - had a completely blank fortnight recently and nearly went haywire. Added up my writing time last week - five hours. But summer is coming, and then I can get up early in the morning - my will-power isn't equal to it in the winter." (Letter to Miles Franklin, 8.9.43)

A room of her own and help with the housework were the solutions, and she had a maid and later, a studio in the garden; but still she felt responsible, attached. It was a two-way stretch, the pull of relationship, the need for periods of solitude, the attempt to find a balance. She was lucky to have a partner who supported her financially and emotionally; Marjorie Barnard, not so fortunate, imagined Eric standing behind Eleanor's chair, urging her on - Write, darling, write.

The Garden

Writing was an intellectual and emotional pleasure; gardening and walking in the bush provided the balance: outdoors, active, testing the body instead of the restless mind. She spent a lot of time in her garden, with its resident bower bird, the gang gangs that dropped pine cones on the roof of her studio, and visiting possums; she was one of the first gardeners to use native plants from the surrounding country, as well as exotics.

The whole high plateau was covered with (dwarf banksias), and their orange flowers had variations of pink and red which she had not seen elsewhere. She closed a hand over one of them gently, thinking that of all flowers only these, and perhaps waratahs, were to be enjoyed by the sense of touch as well as the senses of sight and smell... you could cup you hand over a waratah, or close it round a banksia, and these cool, touch and sturdy flowers gave back to your palm a rubbery resistance. ('Water in Moko Creek', Eleanor Dark, Australia, March 1946)

Eleanor Dark's Country

And down in the valleys grew the trees which belonged to the place - the tall gums tapering like the white masts of ships, the cedar wattles with dark frond-like leaves and clusters of heady, honey-scented blossom, the gnarled angophora... (The Little Company, p235)

They were great bushwalkers, always camping, walking, climbing, exploring. Both of them loved the depth and distance in this mountain country. It wasn't a tourist theme park (give me a blue view without a railing, one of her characters says); they knew it was difficult and even dangerous. In 1937, they found a cave they used as a regular weekend camp. During the war, when the locals were suspicious of their leftwing politics, and local gossips said the cave was a guerilla camp, or that she wrote The Timeless Land in the cave.

She wrote about the Australian bush and its stories, its history of black custodianship and white occupation, about the human need for wilderness, about what it does for the spirit.

Silence ruled this land. Out of silence mystery comes, and magic, and the delicate awareness of unreasoning things....(The Timeless Land, p23)

The country wasn't a passive backdrop to a human landscape; she believed that the country had moulded people as well as people moulding, sometimes exploiting, the country. All that time in the bush meant she knew it in her body as well as her mind. We are part of the country, she said.

.... this conception of ourselves as eternal antagonists of nature instead of harmoniously co-operating parts of it has made us strangers in our own world. (Unpublished essay, Conquest of Nature)

Writing history

Eleanor Dark wrote three historical novels that told the story of the country from first settlement to the crossing of the Blue Mountains: The Timeless Land, Storm of Time, and No Barrier. She spent years researching in the Mitchell Library to make the books historically accurate accounts, then wove in a fictional narrative. The Timeless Land challenged her readers by presenting the arrival of the colonists from the Aboriginal point of view. This was a different way of writing history, some said a new genre, one that made it accessible to a wider audience. It was a history of the people and the land, of black and white, men and women, convicts, free settlers and administrators. A Book of the Month in the US in 1941, it was a best-seller there and, over time, in Australia.

The Studio in the Garden

In 1938, Eleanor built a studio in the garden that made her the envy of other women writers. The letters between Eleanor and Miles Franklin, Nettie Palmer, Jean Devanny , Katharine Susannah Prichard and even the equivocal, sharp-tongued Marjorie Barnard reveal how important these friendships were to women who felt the conflict between family obligations, paid work, social expectations, political commitment and their own desire to get to the desk.

In 1939, the weatherboard cottage was knocked down and the new house built. Eleanor designed it with north-facing windows to catch the sun. Jean Devanny wrote: "Throughout the fine summer days the house lay in a pool of sunshine, of yellow gold."

Varuna sits on the spine of a ridge, looking out over the ridges and valleys, as if giving her a birdseye view across the ranges and valleys to the city and beyond it, the world. Eleanor Dark was in but not of Katoomba.

Eric Dark

Eric Dark was more a part of Katoomba, through his work, his interest in local politics and community projects. Eleanor said she was an independent thinker and a socialist from childhood, taught by her father to question everything. Eric was more conservative; but, seeing what happened to his poorer patients during the depression of the 1930s, he started reading about politics and history, reading his way from the political right to the left.

In 1937, he began to write a series of articles on the social and economic aspects of health. Like other liberal and left thinkers and writers, the Darks were interested in the social experiment of the USSR, and worried by the rise of fascism in Germany and Italy. Eric became active in the local Labour Party and worked on many community projects; he was a founding member of the Doctor's Reform Society, and for many years the chairman of the Australian Council for Civil Liberties.

Eric Dark's publications

Diathermy in General Practive, Sydney, Angus & Robertson, 1932

Medicine and the Social Order, Sydney, F.H. Booth & Son/the author, 1942

Who are the Reds?, Sydney, the Author, 1945

The World against Russia, Sydney, Pinchgut Press, 1948

The Press against the People, Sydney, the author, [1949]

‘Political bias of the Press’, in The Temperament of Generations: Fifty Years of Writing in Meanjin, ed. Jenny Lee, Philip Mead and Gerald Murnane. Melbourne; Meanjin/Melbourne University Press, 1990

In his own words:

On the politics of health:

" A man's health demands that he have enough food, air, light, exercise, rest, useful work, hope for the future, something upon which he can expend his energies to the full. He must have personal dignity, the assurance of a useful place in society, a feeling of economic security... health is bound up with the political and economic structure of society... the present social conditions are such that ill-health is inevitable for a large proportion of the people, and for their children." (Medicine and the Social Order, p7)

On economics:

"We can produce everything that we need to enable all of us to lead full, useful and happy lives; but we cannot distribute it." (Medicine and the Social Order, p 13)

On the freedom of the press:

"... in the democratic State policy should be shaped largely by the force of public opinion, which, in its turn, is shaped by what the public believes to be happening. Obviously, if its press continually feeds it misstatements or untruths, the opinions it forms must be worse than useless... Much has been said lately about the importance of a free Press. I agree that there can be hardly anything in the world more important, but unfortunately we have not got it; our Press is bound hand and foot to the interests of a group of men who for their own selfish purposes are using every device in heir power to present their readers from knowing the truth." (Political Bias of the Press, Meanjin, 1949)

The Queensland Years

The Darks left Katoomba in 1951, looking for a warmer climate, following their son to Queensland. Eleanor felt like a refugee. In 1947, the cold war and the search for subversives had begun. They were both named in federal parliament: Eric as a secret member of the Communist Party, and Eleanor as an underground supporter. Eric received death threats and poison pen letters. Eleanor was troubled about writing; she thought that the rhetoric of the cold war had corrupted the language. Politicians had lost their way, she said; writers, artists, and independent thinkers like Eric, who stood up for their convictions against the odds, were the people who could find new directions.

It is the common habit of mankind - indeed it is necessary to the preservation of his sanity - to compromise at least here and there with the times in which he lives; but it is only out of his occasional refusals to conform, his determination to alter such aspects of them as anger or revolt him, that changes are made - for better or worse. (Caroline Chisholm, in The Peaceful Army)

Eleanor bought a farm at Montville where they grew macadamia nuts and citrus, and she wrote her last two novels. In Lantana Lane, she wrote about living in a farming community around the corner from the world, satirising a materialist, bigger is better, faster is smarter, society. They spent their summers at Varuna and winters in Queensland until 1957, when they went back to Katoomba permanently. She went on writing for more than 10 years, but never finished the family saga novel she was working on. Eric worked as a school medical officer until he was in his 80s. Eleanor died in 1985; Eric stayed on at Varuna till he died at the age of 97 in 1987.

For a woman who called herself apolitical, it's striking how much her work engages with politics, issues, ideas. She and Eric saw politics in terms of moral questions: for Eric it led to social and political activism, for her it became a kind of spiritual quest, and a sense of the social responsibilities of the writer.

Eleanor Dark: Her Work

Her ten published novels are: Slow Dawning (1932), Prelude to Christopher (1934), Return to Coolami (1936), Sun Across the Sky ( 1936), Waterway (1938), The Timeless Land (1941), The Little Company (1945), Storm of Time (1948), No Barrier (1953), and Lantana Lane (1959). They were published in Australia, the UK, the USA, France, Germany, Italy, Sweden.

She published essays about Caroline Chisholm, Australians, the Montville area, and their trip to Central Australia. In the 1920s she had published many poems and stories in literary and women's magazines; later she wrote radio scripts for the ABC. She left unpublished novels from the beginning and end of her life, as well as unfinished essays on women, writing, politics, and the environment. She won awards for two novels, and was awarded the OA in 1978.

Her work has elements of the experimental, multiple voice narratives, a kind of interior monologue, drawing on European modernism when most of her contemporaries ignored it. She brought together an innovative style and the plot devices of the popular novel. Humphrey McQueen said she was for 20 years the most widely read "serious" writer in Australia. An early novel, Prelude to Christopher, was closest to her heart - a controversial and resonant novel, a page-turner, gothic melodrama crossed with novel of ideas, arguments about eugenics, madness and feminism, and a mad, bad, dangerous to know heroine. The books that sold best, and brought her the status of national treasure, were the historical novels, especially The Timeless Land. "A novel of towering stature", the reviewers said, "genuine creative force, with here and there a touch of greatness" , and "the nearest thing we have to a national epic". She was the darling of the historians; Manning Clark credited her with inspiring his work on Australian history.

In her own words

On writing:

"You see the shadow of a place. What place is it? How can you know until you write it down? How can you write it down until you know? This is the burden of the writer's art, to hold himself, poised, receptive, while words and emotions flow together in him and fuse. (Notebooks) On writers and their community. I think that because we are living in such times of stress there's an intellectual striving. The writer feels this like everyone else, and his business is to express it. So when people are searching for an understanding of their problems, they naturally turn to their literature, which gives - or ought to give - a reflection, and perhaps an interpretation, of themselves and their community."(ABC interview, 1944)

On the working conditions of writers:

"...writers can't make writing their real job in life. It seems hardly fair to expect the best from writers, when it's only what's left over of their energy that they can use for their writing - after they've earned their bread and butter. I know of no Australian writer who lives entirely by his writing. (ABC interview, 1944)

More about writing:

" ....writing will be - very disconcertingly - not only a matter of doing, but of being, and when you pore over an unsatisfactory passage you have written, trying to find out what is wrong, you will frequently discover, with a shock of dismay, your own unsatisfactory self looking out of it. ('The Novel', written for the Authors and Writers Handbook)

Varuna, the Writers' Centre

Eleanor Dark chose a life isolated from the city and the world of literary politics and publishing; she was seen as distant, privileged, mysterious. After her death, Michael Dark gave her house to the Eleanor Dark Foundation for the use of Australian writers. Now writers come to Varuna to experience the uninterrupted writing time she knew was so valuable. She said, the story is not just your story:

There is no `beginning' and no`end'... No matter where you begin, someone else has brought the story to that point; no matter where you end, someone takes over from you and carries it on. All you can do is record a fragment of human experience - anywhere, anytime, for every moment gathers in the past and propels the future (The Little Company).

It seems appropriate that her house is a place where so many new stories begin.

- Barbara Brooks July 2000

FURTHER READING

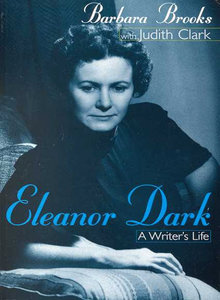

Barbara Brooks with Judith Clark, Eleanor Dark: A Writer's Life. (Macmillan, 1998), available from Varuna, the Writers' House (see below).

Eleanor Dark, Prelude to Christopher. Sydney, Halstead Press, 1999.

Eleanor Dark's other novels are available in libraries.

ELEANOR DARK, A WRITER’S LIFE

Select Bibliography can be found in Eleanor Dark: A Writer's Life.

To purchase a copy of Eleanor Dark, A Writer's Life, email varuna@varuna.com.au.

Cost: for one copy $25, for two copies $40 (includes postage to anywhere in Australia).